Peter Shellenberger

About the work:

Shellenberger’s photographs draw our attention to the gentle hum of nature’s visible and invisible energies, from glowing fireflies to radioactivity to human creativity. His tools include a nineteenth-century, 8x10” camera, old flash bulbs, and uranium in the form vintage Fiesta Ware with orange glaze. An in-depth knowledge about the technical history of photography informs his work as do informal experiments—many, many experiments over the years—employing elements of geometry, physics, and chemistry. Luck and chance play a significant role, too. For Shellenberger, the invention of a process that allows for the creation of an image is as important as the final photographs themselves.

Bio:

Peter Shellenberger is an artist and photographer living and working in Edgecomb, Maine. Peter’s work was recently on view in Seeing What Isn’t There at All Street Gallery in New York. Photographs and films by Shellenberger have been featured in exhibitions at the ICA-MECA&D, Center for Maine Contemporary Art, Space, Concord Art, University of Vermont, University of Southern Maine, and Zero Station. His photographs are in private collections as well as the Judy Glickman Lauder Collection at the Portland Museum of Art.

Peter Shellenberger TIME TRAVEL 2020 analog film/digital print Kodak introduced the Instamatic camera in 1963, along with film cartridges that snapped into place. Film cartridges replaced the cumbersome process of loading film in 35-millimeter cameras. Growing up, I worked in my grandfather’s camera store. I saw first-hand how the Instamatic alleviated the disappointment of many customers whose pictures did not turn out because they failed to load the film properly. 70 million Kodak Instamatic cameras were sold. It was the first camera I had as a kid. The Instamatic was invented a few years before astronauts landed on the moon. Everything seemed possible then. Using this basic camera, complete with a Magicube flash, I’m exploring an imaginative concept inspired by the speed-of-light. The legend suggests that when you look in a mirror, the reflection you see of yourself is younger, by fractions of seconds. A kind of time travel.

Peter Shellenberger MOTEL 2016 analog film/digital print

Peter Shellenberger POOLSIDE 2012 analog film/digital print

Peter Shellenberger Renzo Piano 2017 analog film/digital print In 2017, I was given permission to photograph at a construction site for a building designed by Renzo Piano in Des Moines, Iowa. One night a week I showed up and wandered inside the skeleton and guts of the building. Having built two houses, I was in awe of the lines, shapes, and structural elements. Raw sculpture soon to be covered over, never to be seen or considered again while holding up the building, art, us. With this series, I pay tribute to the beauty beneath the surface, celebrate the bones of structures, and honor the labor it took to build it.

Peter Shellenberger QUEEN ANNE’S LACE II 2023 analog film/digital print I use a nineteenth-century, 8x10 camera to investigate the twenty-first century world. The camera, in all its large-scale boxiness, it’s accordion-shaped bellows, and dramatic top-heavy placement on a sturdy tripod, is often the main attraction. It makes sense. Much drama has been made of a photographer slipping beneath the mysterious black cloth attached to the machine, the sound of a click heard in concert with the pop of a flash bulb. But the key to an old camera is its lens. Lenses were handmade, each one as unique as a fingerprint. Photographers learned the nuanced differences of their lenses, switching them in and out according to the effects they sought in the final prints. My favorite is a 1903 uncoated Bausch and Lomb lens made in Rochester, New York. I work at night, set up the camera, open the aperture, and then, in the distance, set off a powerful flash. This is a minor, but notable, shift to standard practices, when the shutter is open and shut in a matter of seconds. While I make my way to the spot where I set off the flash, the shutter is open, and the film is recording whatever ambient night light reaches it through the lens—the stars, perhaps, or a satellite. After the flash, the shutter remains open, still absorbing light, until I return and close it. In photographic terms, these works are described as being made with a long exposure. This work also involves finding thick, flourishing patches of Queen Anne’s Lace in the late summer. Many folks consider the plant a weed—it’s a prolific self-seeder—while others cultivate them in their gardens or use them medicinally. It is thought that the ingestion of seeds from Queen Anne’s Lace functions as contraception. The resulting prints transform this familiar plant into one that is uncanny and mysterious. The images contain visual metaphors rife in the contemporary imagination: politicians invoking our future as one that will be infused with darkness or light, the out-of-control spread of a virus, the loss of women’s reproductive rights with the recent Supreme Court decision, as well as climate change and chaos caused by human’s interference with nature. Simultaneously, these works offer respite, wonder, and hope in the regenerative force of nature and the miracle of human imagination.

Peter Shellenberger QUEEN ANNE’S LACE II 2023 analog film/digital print I use a nineteenth-century, 8x10 camera to investigate the twenty-first century world. The camera, in all its large-scale boxiness, it’s accordion-shaped bellows, and dramatic top-heavy placement on a sturdy tripod, is often the main attraction. It makes sense. Much drama has been made of a photographer slipping beneath the mysterious black cloth attached to the machine, the sound of a click heard in concert with the pop of a flash bulb. But the key to an old camera is its lens. Lenses were handmade, each one as unique as a fingerprint. Photographers learned the nuanced differences of their lenses, switching them in and out according to the effects they sought in the final prints. My favorite is a 1903 uncoated Bausch and Lomb lens made in Rochester, New York. I work at night, set up the camera, open the aperture, and then, in the distance, set off a powerful flash. This is a minor, but notable, shift to standard practices, when the shutter is open and shut in a matter of seconds. While I make my way to the spot where I set off the flash, the shutter is open, and the film is recording whatever ambient night light reaches it through the lens—the stars, perhaps, or a satellite. After the flash, the shutter remains open, still absorbing light, until I return and close it. In photographic terms, these works are described as being made with a long exposure. This work also involves finding thick, flourishing patches of Queen Anne’s Lace in the late summer. Many folks consider the plant a weed—it’s a prolific self-seeder—while others cultivate them in their gardens or use them medicinally. It is thought that the ingestion of seeds from Queen Anne’s Lace functions as contraception. The resulting prints transform this familiar plant into one that is uncanny and mysterious. The images contain visual metaphors rife in the contemporary imagination: politicians invoking our future as one that will be infused with darkness or light, the out-of-control spread of a virus, the loss of women’s reproductive rights with the recent Supreme Court decision, as well as climate change and chaos caused by human’s interference with nature. Simultaneously, these works offer respite, wonder, and hope in the regenerative force of nature and the miracle of human imagination.

Peter Shellenberger QUEEN ANNE’S LACE II 2023 analog film/digital print I use a nineteenth-century, 8x10 camera to investigate the twenty-first century world. The camera, in all its large-scale boxiness, it’s accordion-shaped bellows, and dramatic top-heavy placement on a sturdy tripod, is often the main attraction. It makes sense. Much drama has been made of a photographer slipping beneath the mysterious black cloth attached to the machine, the sound of a click heard in concert with the pop of a flash bulb. But the key to an old camera is its lens. Lenses were handmade, each one as unique as a fingerprint. Photographers learned the nuanced differences of their lenses, switching them in and out according to the effects they sought in the final prints. My favorite is a 1903 uncoated Bausch and Lomb lens made in Rochester, New York. I work at night, set up the camera, open the aperture, and then, in the distance, set off a powerful flash. This is a minor, but notable, shift to standard practices, when the shutter is open and shut in a matter of seconds. While I make my way to the spot where I set off the flash, the shutter is open, and the film is recording whatever ambient night light reaches it through the lens—the stars, perhaps, or a satellite. After the flash, the shutter remains open, still absorbing light, until I return and close it. In photographic terms, these works are described as being made with a long exposure. This work also involves finding thick, flourishing patches of Queen Anne’s Lace in the late summer. Many folks consider the plant a weed—it’s a prolific self-seeder—while others cultivate them in their gardens or use them medicinally. It is thought that the ingestion of seeds from Queen Anne’s Lace functions as contraception. The resulting prints transform this familiar plant into one that is uncanny and mysterious. The images contain visual metaphors rife in the contemporary imagination: politicians invoking our future as one that will be infused with darkness or light, the out-of-control spread of a virus, the loss of women’s reproductive rights with the recent Supreme Court decision, as well as climate change and chaos caused by human’s interference with nature. Simultaneously, these works offer respite, wonder, and hope in the regenerative force of nature and the miracle of human imagination.

Peter Shellenberger QUEEN ANNE’S LACE I 2020 analog film/digital print I use a nineteenth-century, 8x10 camera to investigate the twenty-first century world. The camera, in all its large-scale boxiness, it’s accordion-shaped bellows, and dramatic top-heavy placement on a sturdy tripod, is often the main attraction. It makes sense. Much drama has been made of a photographer slipping beneath the mysterious black cloth attached to the machine, the sound of a click heard in concert with the pop of a flash bulb. But the key to an old camera is its lens. Lenses were handmade, each one as unique as a fingerprint. Photographers learned the nuanced differences of their lenses, switching them in and out according to the effects they sought in the final prints. My favorite is a 1903 uncoated Bausch and Lomb lens made in Rochester, New York. I work at night, set up the camera, open the aperture, and then, in the distance, set off a powerful flash. This is a minor, but notable, shift to standard practices, when the shutter is open and shut in a matter of seconds. While I make my way to the spot where I set off the flash, the shutter is open, and the film is recording whatever ambient night light reaches it through the lens—the stars, perhaps, or a satellite. After the flash, the shutter remains open, still absorbing light, until I return and close it. In photographic terms, these works are described as being made with a long exposure. This work also involves finding thick, flourishing patches of Queen Anne’s Lace in the late summer. Many folks consider the plant a weed—it’s a prolific self-seeder—while others cultivate them in their gardens or use them medicinally. It is thought that the ingestion of seeds from Queen Anne’s Lace functions as contraception. The resulting prints transform this familiar plant into one that is uncanny and mysterious. The images contain visual metaphors rife in the contemporary imagination: politicians invoking our future as one that will be infused with darkness or light, the out-of-control spread of a virus, the loss of women’s reproductive rights with the recent Supreme Court decision, as well as climate change and chaos caused by human’s interference with nature. Simultaneously, these works offer respite, wonder, and hope in the regenerative force of nature and the miracle of human imagination.

Peter Shellenberger QUEEN ANNE’S LACE I 2020 analog film/digital print I use a nineteenth-century, 8x10 camera to investigate the twenty-first century world. The camera, in all its large-scale boxiness, it’s accordion-shaped bellows, and dramatic top-heavy placement on a sturdy tripod, is often the main attraction. It makes sense. Much drama has been made of a photographer slipping beneath the mysterious black cloth attached to the machine, the sound of a click heard in concert with the pop of a flash bulb. But the key to an old camera is its lens. Lenses were handmade, each one as unique as a fingerprint. Photographers learned the nuanced differences of their lenses, switching them in and out according to the effects they sought in the final prints. My favorite is a 1903 uncoated Bausch and Lomb lens made in Rochester, New York. I work at night, set up the camera, open the aperture, and then, in the distance, set off a powerful flash. This is a minor, but notable, shift to standard practices, when the shutter is open and shut in a matter of seconds. While I make my way to the spot where I set off the flash, the shutter is open, and the film is recording whatever ambient night light reaches it through the lens—the stars, perhaps, or a satellite. After the flash, the shutter remains open, still absorbing light, until I return and close it. In photographic terms, these works are described as being made with a long exposure. This work also involves finding thick, flourishing patches of Queen Anne’s Lace in the late summer. Many folks consider the plant a weed—it’s a prolific self-seeder—while others cultivate them in their gardens or use them medicinally. It is thought that the ingestion of seeds from Queen Anne’s Lace functions as contraception. The resulting prints transform this familiar plant into one that is uncanny and mysterious. The images contain visual metaphors rife in the contemporary imagination: politicians invoking our future as one that will be infused with darkness or light, the out-of-control spread of a virus, the loss of women’s reproductive rights with the recent Supreme Court decision, as well as climate change and chaos caused by human’s interference with nature. Simultaneously, these works offer respite, wonder, and hope in the regenerative force of nature and the miracle of human imagination.

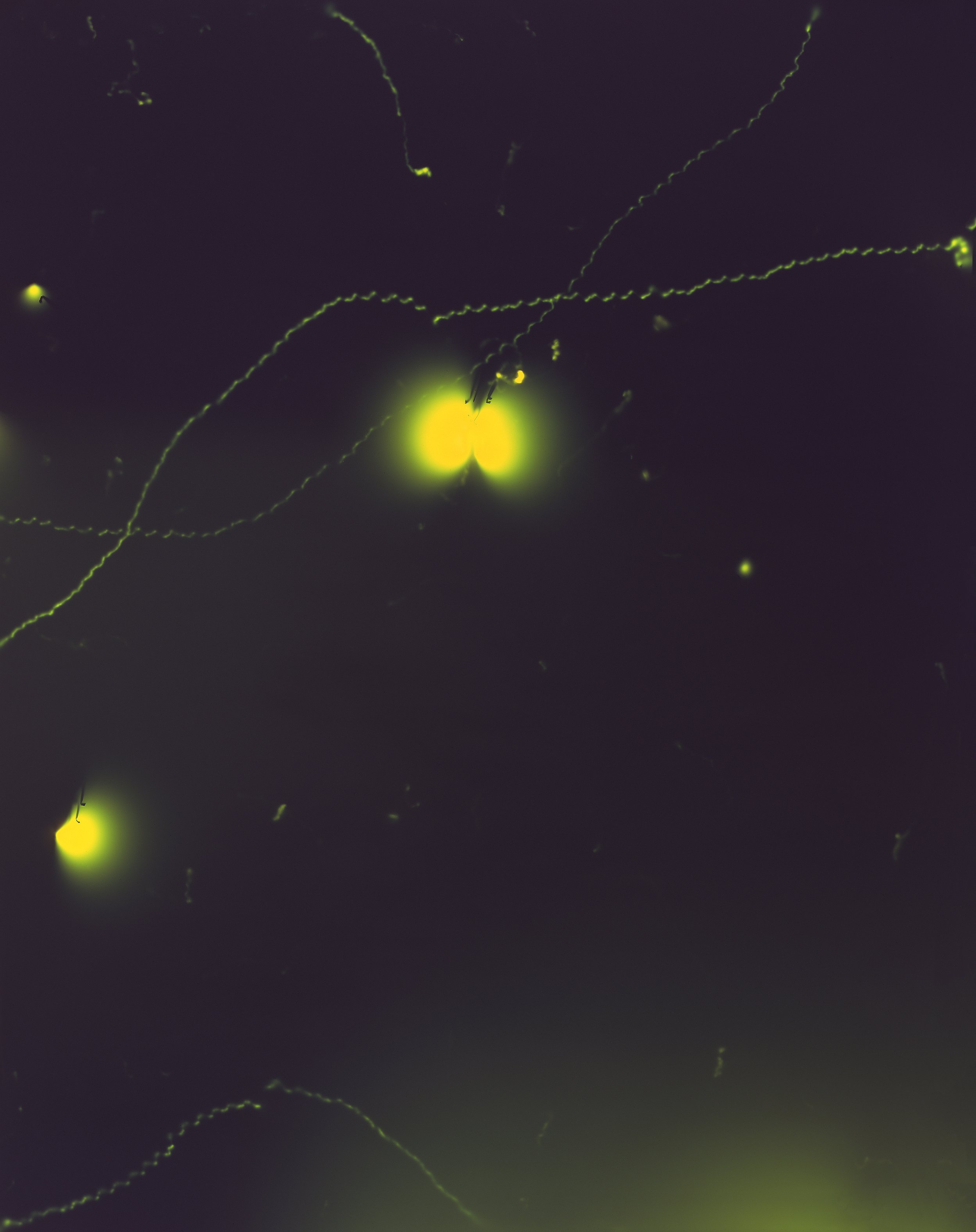

Peter Shellenberger FIREFLIES analog film/digital print When asked if I use a camera to make my firefly photographs, the short answer is yes. However, the nineteenth camera functions simply as a box, a container. The shutter, aperture, lens are do not play a role. The one function I do utilize is the film back, designed to hold 8x10” sheets of unexposed film. The large camera is roomy enough for 3-4 fireflies to spend the night. Lanterns flashing, they expose the film, resulting in random luminescent patterns. After a night in the camera, they are released the next morning. Look closely, and you can see a firefly leg, wing, or head in the photographs. Each year, when the insects show up in the yard in July, I make 3-4 firefly prints. A couple of unique photographs combines two organic energies: a fireflies’ bioluminescence and uranium’s radioactivity. The red-orange glaze made for Fiesta Ware in the 1930s and 40s contains uranium oxide. After about two years experimenting, I discovered the radiation in the orange glaze was strong enough to expose film, resulting in glowing purple “nuclear” autoradiographs.

Peter Shellenberger FIREFLIES analog film/digital print When asked if I use a camera to make my firefly photographs, the short answer is yes. However, the nineteenth camera functions simply as a box, a container. The shutter, aperture, lens are do not play a role. The one function I do utilize is the film back, designed to hold 8x10” sheets of unexposed film. The large camera is roomy enough for 3-4 fireflies to spend the night. Lanterns flashing, they expose the film, resulting in random luminescent patterns. After a night in the camera, they are released the next morning. Look closely, and you can see a firefly leg, wing, or head in the photographs. Each year, when the insects show up in the yard in July, I make 3-4 firefly prints. A couple of unique photographs combines two organic energies: a fireflies’ bioluminescence and uranium’s radioactivity. The red-orange glaze made for Fiesta Ware in the 1930s and 40s contains uranium oxide. After about two years experimenting, I discovered the radiation in the orange glaze was strong enough to expose film, resulting in glowing purple “nuclear” autoradiographs.

Peter Shellenberger FIREFLIES analog film/digital print When asked if I use a camera to make my firefly photographs, the short answer is yes. However, the nineteenth camera functions simply as a box, a container. The shutter, aperture, lens are do not play a role. The one function I do utilize is the film back, designed to hold 8x10” sheets of unexposed film. The large camera is roomy enough for 3-4 fireflies to spend the night. Lanterns flashing, they expose the film, resulting in random luminescent patterns. After a night in the camera, they are released the next morning. Look closely, and you can see a firefly leg, wing, or head in the photographs. Each year, when the insects show up in the yard in July, I make 3-4 firefly prints. A couple of unique photographs combines two organic energies: a fireflies’ bioluminescence and uranium’s radioactivity. The red-orange glaze made for Fiesta Ware in the 1930s and 40s contains uranium oxide. After about two years experimenting, I discovered the radiation in the orange glaze was strong enough to expose film, resulting in glowing purple “nuclear” autoradiographs.

Peter Shellenberger ACROBATS 2022 Autoradiograph The red-orange glaze made for Fiesta Ware in the 1930s and 1940s contains uranium oxide, the same uranium used to make the atomic bomb. In fact, the Fiesta Ware company’s supply of uranium was confiscated by the U.S. government to make the first atomic bombs. After about two years experimenting, I discovered that the uranium in the orange glaze remains radioactive in the dinnerware and that I can use this radioactivity to create glowing purple “nuclear” autoradiographs. (It remains unclear why the prints result in the color purple.) I featured Cracker Jack toys—the same vintage as the radioactive Fiesta ware—in my first autoradiographs. Recently I used computer chips from Atari video games (circa 1978-1980's), the prints titled with the names of the old games. The radiation functions like an x-ray, revealing the physical make-up of the chips’ intricate interiors. I am drawing parallels in this series between radiation and computer technology, two invisible powers that were unleashed, with little knowledge of their potential to significantly transform our world. Influenced, in part, by Chris Marker's film La Jetée, my work metaphorically channels messages sent from the future to the past, to speak to human experience now.

Peter Shellenberger ROLLER SKATER 2012 Autoradiograph The red-orange glaze made for Fiesta Ware in the 1930s and 1940s contains uranium oxide, the same uranium used to make the atomic bomb. In fact, the Fiesta Ware company’s supply of uranium was confiscated by the U.S. government to make the first atomic bombs. After about two years experimenting, I discovered that the uranium in the orange glaze remains radioactive in the dinnerware and that I can use this radioactivity to create glowing purple “nuclear” autoradiographs. (It remains unclear why the prints result in the color purple.) I featured Cracker Jack toys—the same vintage as the radioactive Fiesta ware—in my first autoradiographs. Recently I used computer chips from Atari video games (circa 1978-1980's), the prints titled with the names of the old games. The radiation functions like an x-ray, revealing the physical make-up of the chips’ intricate interiors. I am drawing parallels in this series between radiation and computer technology, two invisible powers that were unleashed, with little knowledge of their potential to significantly transform our world. Influenced, in part, by Chris Marker's film La Jetée, my work metaphorically channels messages sent from the future to the past, to speak to human experience now.

Peter Shellenberger ATARI 2024 I Want my Money Autoradiographs The red-orange glaze made for Fiesta Ware in the 1930s and 1940s contains uranium oxide, the same uranium used to make the atomic bomb. In fact, the Fiesta Ware company’s supply of uranium was confiscated by the U.S. government to make the first atomic bombs. After about two years experimenting, I discovered that the uranium in the orange glaze remains radioactive in the dinnerware and that I can use this radioactivity to create glowing purple “nuclear” autoradiographs. (It remains unclear why the prints result in the color purple.) I featured Cracker Jack toys—the same vintage as the radioactive Fiesta ware—in my first autoradiographs. Recently I used computer chips from Atari video games (circa 1978-1980's), the prints titled with the names of the old games. The radiation functions like an x-ray, revealing the physical make-up of the chips’ intricate interiors. I am drawing parallels in this series between radiation and computer technology, two invisible powers that were unleashed, with little knowledge of their potential to significantly transform our world. Influenced, in part, by Chris Marker's film La Jetée, my work metaphorically channels messages sent from the future to the past, to speak to human experience now.

Peter Shellenberger ATARI 2024 Name This Game Autoradiographs The red-orange glaze made for Fiesta Ware in the 1930s and 1940s contains uranium oxide, the same uranium used to make the atomic bomb. In fact, the Fiesta Ware company’s supply of uranium was confiscated by the U.S. government to make the first atomic bombs. After about two years experimenting, I discovered that the uranium in the orange glaze remains radioactive in the dinnerware and that I can use this radioactivity to create glowing purple “nuclear” autoradiographs. (It remains unclear why the prints result in the color purple.) I featured Cracker Jack toys—the same vintage as the radioactive Fiesta ware—in my first autoradiographs. Recently I used computer chips from Atari video games (circa 1978-1980's), the prints titled with the names of the old games. The radiation functions like an x-ray, revealing the physical make-up of the chips’ intricate interiors. I am drawing parallels in this series between radiation and computer technology, two invisible powers that were unleashed, with little knowledge of their potential to significantly transform our world. Influenced, in part, by Chris Marker's film La Jetée, my work metaphorically channels messages sent from the future to the past, to speak to human experience now.